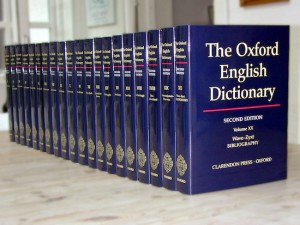

Reading dictionaries is fun. I especially like the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), along with its two companions, the Compact Oxford English Dictionary, and the Compact Oxford Thesaurus.

Reading dictionaries is fun. I especially like the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), along with its two companions, the Compact Oxford English Dictionary, and the Compact Oxford Thesaurus.

Seriously, this isn’t nerdy at all. It’s really entertaining.

For example, my brother Will told me the other day that he had an interesting experience. He was studying the OED, and he noticed that many of the words aren’t currently in wide use around the English-speaking world.

This intrigued me, so I went to the OED to see for myself. The truth is, it is downright amazing how many words have gone out of vogue.

Do you know what a buhl is? Or a bourn? How about a froideur? A ratbag? Or a virago? Maybe you know the definitions to all these words. Maybe you use them several times a day in your ordinary language. Or not. I’m not saying that these words were ever in common usage, except “ratbag” among certain classes and decades in England.

But here’s the one that really got to me. In the Compact OED, the word “free” has an interesting set of definitions. Here they are:

- able to do what one wants; not under the control of anyone else.

- not confined, obstructed, or fixed.

- not having or filled with things to do.

- not occupied or in use.

- not containing or affected by something undesirable.

- available without charge.

- using or spending something without restraint.

- behaving or speaking without restraint.

- not following the normal conventions.

The striking thing about all these definitions is that none of them say anything about duties, responsibilities, or the price of being free.

In fact, they seem to universally communicate the opposite: freedom is free, it costs nothing, free governments aren’t limited in any way, free government can spend and spend without constraint, freedom is available without charge.

I know I’m reading a little into this, but the definitions all lean in this direction.

The definition of “freedom” carries the same overtone and insinuation. It’s all about rights, lack of restraints, having powers and privileges. Not one word about how we got these benefits. Not one word about responsibilities. Not one word about sacrifice. Not one word about the hard work necessary to establish and maintain a free society. Not one word about the cost of losing it.

I can’t help but notice how these dictionary definitions are almost exactly what most people in society today seem to think of freedom. They think freedom should be free. They think freedom should just happen, without sacrifice or hard work. They treat it like a permanent benefit, like something that can never be taken away.

And the dictionary seems to reinforce this view. The sentences used as examples in the dictionary were particularly poignant:

“I spent my free time shopping.”

“Tax-free.”

“Clothing that allows maximum freedom of movement.”

“The dog had the freedom of the house.”

This is what freedom has come to mean for too many people. Something for nothing. Something impossible to lose. A freebie.

If that’s the way we continue to approach freedom, we’re going to lose it. We should be closely studying the following: our duties, our responsibilities, the sacrifices necessary to remain a free people, the history of people paying the ultimate price for freedom. Freedom isn’t free. Not even close.

We don’t want to be a freebie nation, we want to be free — and freedom only comes at a very high price. It’s worth it. But it’s also work.

And we can’t leave it up to the experts, officials, or any other group. Freedom has to be earned. I like the Compact OED definition of the word earn:

“receive deservedly for one’s behavior or achievements.”

The truth is, that’s a very accurate definition of how people become and stay free.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Among many other works, he is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, The Coming Aristocracy, and FreedomShift: 3 Choices to Reclaim America’s Destiny.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

This is a great point, Oliver! The dictionary is just one example of the principles of freedom being lost in our modern day. The omissions and indoctrination in our education system, media bias (or blatant untruth), the mutation of our government from a republic to a democracy (term used loosly), and our economy becoming the most ‘un-free’ free market in history are all signs of a society heading for the bottom end of the ‘cycle of the body politic’. Even if we can change the mind of some people and get the ship patially turned in a better direction, how many generations do you think before effective change is actually implemented? Are we planting trees in which the shade we will never sit?

True, tragically true.

You know, in my earlier years, I ( for reasons I will not delve into here) had a rather unsocial lifestyle, and so I frequently ended up reading a particular dictionary (which I still have, it’s the only one in print I have found that gives complete etymologies, or word-origin traces) and encyclopedias, which has now become impractical. But if memory serves, freedom is a forshortening of ‘free dominion’, i.e. unrestricted rule. So here comes the question – rule over what? You see, freedom has something called a ‘scope’, which is a term I use in the technical sense that it possesses in law and programming. A scope is a specific attribute that defines something’s sphere of influence or applicability.

What is the scope of freedom? Is everyone to have universal, unrestricted freedom? That notion breaks down rapidly in the face of logic, because if people have freedom to harm each other without cause or deprive each other of liberty, then we have arrived at no other than the law of the jungle, the “survival of the fittest”, as Darwin phrased it. This is not how civilizations are built or maintained.

Is freedom the lisense to do anything that doesn’t affect or bother someone else? Do I have the freedom to play my music at a decibel level that upsets my neighbor’s concentration or damages their hearing? A better question – should I be prohibited from playing music at a level that damages my own hearing? And if not, who will enforce such an ordinance, and how?

You see, the scope of freedom is vitally important to understand and define, because without it, society is subject to the swinging of the Power Pendulum ( http://orrinwoodwardblog.com/2013/08/30/western-civilization-the-power-pendulum/ ) , where a cyclical struggle is set up between rigid restriction and license and uncertainty. A culture of no restraint has no security or stability; conversely, a culture with no liberty has no creativity or innovation, because challenging the established order is disallowed and either dismissed or punished.

So, what is the scope of freedom? Instead of answering the question, I will pose another one against it: If one has not mastered oneself, what cause does one have to seek mastery over others? And if one has attained a degree of self-mastery, does that person have a right to extend control over others?; or rather do they have a duty to model and mentor others to move up towards their level?

If you are patient enough to watch the original classic “The Day the Earth Stood Still” (1951), the end involves a proposal to place Earth under the same gov’t. that their neighboring civilizations have: a police state run and enforced by pitiless, impartial robots. The proposal itself aside, the line that catches in my mind is this: “This does not involve giving up any freedom: only the freedom to act irresponsibly.” Absolute freedom leads to destabilizing chaos, and administered rights wither into totalitarianism. The price of winning freedom is often blood and tragic sacrifice. The price of maintaining it is just as often often mundane and undramatic – that of developing self-discipline and wise habits.