Confidence in human institutions is fading.

Confidence in human institutions is fading.

Modernism is slowly losing its foothold as many human beings are seeing that institutions are unable to deliver the happiness they claim to provide.

In fact, many are beginning to see the authoritarian nature of most human institutions as a limit to their pursuit of happiness, an encroachment on their liberty, and as diminishing the value of their lives.

Over the past one hundred years, as this process has slowly taken hold, two political philosophers have described what the future (now the present) has in store and attempted to show us what options there are in a postmodern world.

These two main branches of postmodernism can be described as libertarian postmodernism (individualism) and humanistic postmodernism (a sense of responsibility to care for and better the situation of self and others).

These two philosophers are Ayn Rand, promoting the individualistic branch, and Leo Tolstoy, promoting the humanistic branch.

Ayn Rand

Ayn Rand’s influence has been profound.

Ayn Rand’s influence has been profound.

Her two most influential works, The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, have laid the foundation for the anti-institutional, pro-individual philosophy that is at the heart of a go-it-alone, laissez-faire attitude that undergirds much of a rising Western, and especially American, movement.

This is demonstrated by a Random House poll asking readers to rank their top 100 novels. Four of the top eight spots are occupied by Ayn Rand works, with Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead topping the list.

This list shows that those who read really enjoy (and apparently accept) the writings, ideas, and philosophies of Ms. Rand.

Her political philosophy is growing quickly and exerting profound influence on thought and attitude, albeit slower effect on public policy.

This philosophy, however, is problematic because Rand sees society as being made up of individuals who are exclusively seeking their own interest without regards to the interest of society or future generations.

Morality, according to Rand, is doing what reason discovers. Because man is fundamentally a rational animal, reason is what man needs to live the good life.

Sacrificing reason on the altar of mysticism or socialism is the greatest immorality.

Each individual has his own capacity and conclusions. They may be wrong, but they are his and thus he has responsibility to follow them and discover when they are wrong.

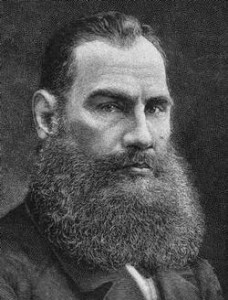

Leo Tolstoy

Leo Tolstoy, on the other hand, sees society as being made up of people who naturally desire to do good, who behave badly because of what they are taught and how they are influenced by their environment, and who must see a duty to help others and alleviate suffering.

Leo Tolstoy, on the other hand, sees society as being made up of people who naturally desire to do good, who behave badly because of what they are taught and how they are influenced by their environment, and who must see a duty to help others and alleviate suffering.

He believes, with other humanistic postmodernists (i.e. Ruiz) that what we assume to be reality is actually the nightmarish dream perpetuated by the previous generation, inculcating the rising generation with a pervasive sense of fear and judgment.

He also sees it as mankind’s responsibility to leave the world a better place for future generations.

Because Tolstoy’s writings have very definite anti-government and even anti-church indictments (not unlike Rand’s; the difference being his were written in Russia and hers in America), his works were neither widely circulated nor well received.

However, his book The Kingdom of God is Within You was found, read, and internalized by Mohandas K. Gandhi while studying law in Great Britain.

That book, together with his Hindu background and the New Testament (specifically the teachings of Jesus Christ in the Gospels) laid the foundation for Gandhi’s “non-resistance of evil” doctrine that ended British colonial rule in India, began the weakening of the caste system there, and prepared South Africa for the end of apartheid.

There is a postmodern commonality in the philosophies of Tolstoy and Rand in their conviction that institutions (i.e. governments, churches and other modernistic structures) cannot solve the problems of the world, but that they are actually at the heart of most of the problems.

However, there is polar opposition between the two philosophies regarding the view of humanity and human nature and the role of the individual within that humanity.

They are also opposed in the allegiance they promote.

Rand promotes unflagging and focused allegiance to self and self alone.

Tolstoy promotes the profoundest allegiance to God, subjecting self, “society”, government, and all other “ikons” that might distract, to that Ultimate allegiance.

However, Tolstoy understands the need for the individual to know who he is and be true to who he truly is: a human being with a powerful divine nature.

Rand is purposefully carnal and unapologetically brutal. Tolstoy is deeply spiritual and devoutly peaceful.

Epistemology

Randian epistemology is reason.

Emotion and feeling are not teachers, but weaknesses to be overcome. Human nature is independent of anything but individual choice and the ultimate good is excelling (Greek and republican Roman virtue).

Sex is an act of pure pleasure without a right or wrong about it as long as true loyalty (deserved loyalty demonstrated by reciprocal selfishness) isn’t violated.

Concern for others and their well-being is seen as the ultimate evil, unless it brings one joy.

Tolstoy’s epistemology is also reason, but with faith in the truth and power of the words of the Singular Individual of Jesus Christ.

Emotion and feeling are important teachers of what is right and wrong. Human nature is good, turned evil by environmental influences and choices that are almost determined by prior choices and situations.

The ultimate good is love. Within all is a divine portion that needs sustenance by love.

Sex is right only in the right circumstances. In all others it is degrading and damaging to the soul.

Concern for others is highly desirable and necessary to making the world a more joyous and happy place.

These views are powerfully and clearly articulated in Tolstoy’s novel Resurrection.

Both are clear about the power of the individual to accomplish change (although “truth” is much less of an object for Rand, to whom the most important value is “right,” meaning “acting” according to one’s complete self-interest).

Rand idolizes individuals who are powerful because they concern themselves exclusively with excellence that satisfies their reason and free will — they have made their own soul.

Tolstoy idolizes individuals who are powerful because they concern themselves with acting in love and compassion and being true to that most fundamental component within them — their divine portion, allowing God to expand their soul.

As modernism continues its slow but sure deterioration, we have the opportunity to help define what worldviews come next.

Our obligation, as individuals, families, and communities who value liberty, virtue, and kindness, is to find, learn, mold, and promote the worldview that helps move us to that end.

One decision will likely be whether to promote divine-centered and relationship-based postmodernism or to promote the rapidly-rising individualistic libertarian postmodernism.

****************

Mike Wilson received his B.S. degree in Chemistry from Brigham Young University and pursued graduate work at the University of California, San Diego, where he earned a M.S. degree in Biomedical Sciences prior to obtaining his M.D. at the UCSD School of Medicine.

Mike Wilson received his B.S. degree in Chemistry from Brigham Young University and pursued graduate work at the University of California, San Diego, where he earned a M.S. degree in Biomedical Sciences prior to obtaining his M.D. at the UCSD School of Medicine.

He lives in Cedar City, Utah with his wife Jenni and their six children and practices emergency medicine in St. George, Utah while working on a Ph.D. in Constitutional Law at George Wythe University. He is also an Associate Mentor at GWU.

Mike’s passion is promoting idea that the common man has power and capacity to affect grand change in the world through true principles of love, goodness, and virtue. Because of his Jeffersonian trust in the common man, he considers himself a “little d” democrat (an ideal, not a political party).

He believes that the cause of liberty is founded essentially in widespread powerful education, checks on power, and promotion of virtue and goodness. Force is never a real solution to problems for Mike and the statesman’s role is to understand the ideal, see where society is, and then put himself in a position to move society in the direction of the ideal.

Question Mike: In the new post-modern context could the nature of voting be overly individualistic? I wonder if the voting (republican) system is too hard-set.

Example from the judicial system: We cut relations off with ‘opinions of the court’ by not allowing the more collaborative and healing results that can occur through mediation. Criminal law seems to be in the same boat, where reparation and mercy could be infused with a more “prosumer” (Toffler’s word) approach.

Nice analysis. I like Ayn Rand when it comes to basic economic principles, but I find that her philosophy is seriously flawed.

Truly, in the liberty movement there is a great divide forming.

Allen,

What do you mean by “too hard-set”? I do think that our current voting (at least by paleo-conservatives and libertarians) is very individualistic. I don’t know that the nature of voting is of itself individualistic, except that the vote, unless intentionally so, is rarely tied to community, much less to generational thinking. These are the distinctions between Rand and Tolstoy again. Rand assumes that the greater good will result from the individualistic approach. Tolstoy demands of humanity a broader view of including community in our considerations while not sacrificing who we TRULY are (as opposed to Rand’s view of what we carnally are).

David,

Thanks. The divide can only be settled by uniting and healing, which I think is what Allen is saying. As we persist in thinking that our actions don’t have wide-ranging consequences for others as well as ourselves, we will be unable to resolve the discord.

I think you interpreted the hard-set meaning well. It seems like the voting process needs to involve or connect the voters together. There’s very little life in it. It doesn’t involve interconnected learning or personal improvement. Once you vote its over and you have, I think, falsely assumed that your input will solve the problem or, if your party didn’t get in, you assume your vote just didn’t work; either way you are not obligated anymore. Most importantly there was no real change in you and the vote doesn’t often help join you together with your community and your personal relations. Furthermore, with all of that effort and money expended very little good came of it. So I suppose with “hard-set” I was referring to the cold, slow-moving, lifeless forms of the disconnected industrial age.

I don’t know why this article triggered voting as a topic where these two epistemologies could converge. But before tying it back in, I had some additional thoughts about the hard-set feeling.

Voting also seems to be hard-set into party structures. Often times the needed solution reaches well beyond what a polarized debate-based dialogue can produce. We keep saying that we need to reach across the isle and include the other party, but we do not often leave the debate context. We don’t approach it from a true interdisciplinary or scenario based context. I believe that it may be the individual nature of the actual voting (somewhat selfish) and by default the campaigning process that perpetuates the problem.

Voting by itself may have worked in the old-times but our day is demanding flexibility, its also demanding more of us in education. The old form of disconnected voting and learning doesn’t seem to work for us as well. Today learning involves doing and becoming, it involves seeing the big picture and getting involved. Its faster more thorough, more complete and personal. Voting seems to need the same shift. I didn’t realize how much I had to say about this. Thanks for your patience and for getting this far.

The Randian way feels cold and lifeless, devoid of the personality-depth that comes from family, community and God. It doesn’t connect us more completely with our relationships. Tolstoy’s postmodern approach seems to allow for this new “prosumer” connected approach.