Most people in the modern world tend to see human history as a long progress from tribal societies to the Agrarian Revolutions that brought communities and cities and civilization, to the Industrial Revolution’s advanced technology, and now further progress into the Information Age.

Most people in the modern world tend to see human history as a long progress from tribal societies to the Agrarian Revolutions that brought communities and cities and civilization, to the Industrial Revolution’s advanced technology, and now further progress into the Information Age.

From this view, education and careers have changed to keep up with the progress of mankind.

Not surprisingly, many of the most important great books on freedom take a different approach.

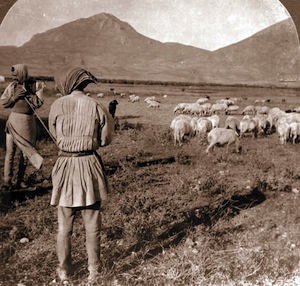

For example, according to Hebrew scholar Yoram Hazony, a central theme of the Biblical message is that the “shepherd’s ethics” are superior to the agrarian-based civilizations.

This turns the whole view of modern progress on its head. If tribal culture is better than cities and farming, and farming was closer to the right way than industrialized-technological society, then our modern system is far off base.

But this isn’t an anti-technology view at all.

Hazony wrote:

In the [Biblical] History, the shepherd and the farmer are taken as representing contrasting ways of life, and two different kinds of ethics, which come into sharp conflict time and again — especially in the stories of Abraham, Joseph, Moses and David.”

In fact, this conflict is the source of the first great Biblical battle, between Cain and Abel. Hazony continues:

“God’s preference for the ethics of the shepherd is therefore portrayed as being prior to all of the laws or commands God gives to man…

“Ancient narratives are usually about heroes of royal or noble birth. But the biblical History of Israel is something quite different. It is a story about shepherds. Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph and his brothers, Moses, and even David, are all shepherds…

“Mankind’s life after Eden begins with the murder of Abel, a shepherd, by his brother Cain, who was a farmer; and this because God accepted the shepherd’s sacrifice but rejected that of a farmer. Abraham, the first Jew, is born in the urban metropolis of Ur, but we are told that he leaves it to take up the nomadic life of a shepherd because God himself wished him to do this.”

Joseph’s dreams are of raising grain, farming, but his move to the city brings the Israelites into slavery. Moses escapes the cities of Egypt to become a nomad, and then helps his people do the same. David the shepherd boy is one of the greatest icons of righteousness; David the sophisticated, urban king is the opposite.

These themes continue throughout the Bible. What is the point?

Hazony says that the Biblical narrative repeatedly presents the reader with a choice between two sets of lifestyles. The text never directly outlaws cities, nor openly promotes being a shepherd, but the stories do this over and over.

The Bible creates a clear distinction between two ways of life, and it shows that God consistently prefers one over the other.

The farmer life, tied to the land, and the life of those in the cities built around agriculture, all lead to a certain set of values.

Hazony suggests that this type of life is built on submission — submission to the land, to tradition, to the government, to the careers of earning one’s bread each year.

In contrast, Hazony shows that the tribal-nomadic life is based on “ingenuity and daring,” resisting submission, taking “initiative,” and seeking freedom and progress for self and family.

The point isn’t that God likes tribal herding any more than tilling the soil. No, what He prefers are people who are independent and free, not cloistered and submissive.

Note that both of the two lifestyles include people who are obedient and others who are not. Sin and morality are present in both. So the message isn’t that herding is righteous and cities are evil.

The point of this Biblical narrative appears to be that God likes freedom, and also that he dislikes the lack thereof.

This is a challenging concept for many moderns, because we have been taught to read things rotely, not symbolically. For the ancients, the symbolism of the stories was clear: God prefers man to be free.

The corollary of this is even more interesting. When the Israelites lost their freedom, it was the result of their search for food and security as provided by the cities and their governments.

It wasn’t so much bread and circuses as bread and safety. This same point appears again later in the Bible in Samuel’s plea with the people to avoid having a king.

But the desire for a government to provide stable food and easy security is too strong — even at the cost of freedom. Of course, at first the people think they’re only going to give up a little freedom. But that isn’t how governments work.

In short, a political philosophy emerges in the Biblical story: the power of the state is to be held in suspicion. The Tower of Babel, Egypt, Assyria, Babylonia and Canaan are dangerous to the people specifically because they are dangerous to freedom.

In Hazony’s words:

“The message here is unequivocal: God loves those who resist the injustice of the state.”

This is deep.

Hazony points out that Israel’s dilemma is real. The nomadic way is often dangerous and the people sometimes go hungry.

In the Biblical story, the solution is to take on a king, but to be sure that the power of the government is effectively limited.

This same pattern dominated the history of Greece, Rome and medieval Europe. The battle between the “submitters” and “innovators” defined much of what happened in these nations.

Likewise, in his 1787 book on British history, the Scottish thinker John Millar suggested that the big challenge in early England was the conflict between tribal Saxons who built their lives around herding, and the feudal lords who hired the people and put them to farming — and then slowly enslaved them.

This is the same pattern as the Biblical narrative. In fact, Jefferson’s suggestion to the Indian tribes that their future success relied upon their willingness to turn from hunting and herding to farming follows this model as well.

The early American government, as quick as it was to mistrust British rule, thought itself the best option for all people in America, even those who were already free.

Governments generally adopt this view. But the American founding came at a time where things really were changing. As Gary Keller wrote:

“Jared Diamond’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies illustrates how farm-based societies that generated a surplus of food ultimately gave rise to professional specialization.”

When a few people could produce enough food for all, the rest were initially freed up to do other things. The good news was that this led to advances in technology, art, literacy and science.

The bad news was surprising: this new age of specialization also created managers and politicians.

Managers were a negative because they set out to get rid of everyone’s newly-found free time. Keller continues:

“This freedom from having to forage or farm allowed people to become scholars and craftsmen. Some worked to put food on our tables, while others built the tables.

“At first, most people worked according to their needs and ambitions. The blacksmith didn’t have to stay at the forge until 5 p.m.; he could go home when the horse’s feet were shod. Then 19th Century industrialization saw for the first time large numbers working for someone else.

“The story become one of hard-driving bosses, year-round work schedules, and lighted factories that ignored dawn and dusk.”

Sweatshops of underfed children working all day were a reality in a number of cities. Instead of privately-owned farms and shops supporting families, families were now expected to sacrifice to support the needs of businesses and corporations.

Where early agrarianism increased general freedom, over time it centralized financial power, became industrialized, and returned most of the regular people back to lives of submission.

Employees had it better than serfs, and serfs had it better than slaves — but all were ultimately caught in the “submissive” lifestyle rather than the Abrahamic values of initiative, innovation and independence.

Moreover, as democracy spread, the majority of people took the submissive approach and felt of sense of trust for and dependence on their governments.

The innovative types retained their mistrust for too much government, but they were part of the minority.

Simultaneously, the rise of specialized careers created experts on government. Politicians and bureaucrats took over governance the same way managers dominated commerce.

The regular people became too busy making a living to be bothered with freedom and keeping government in its proper place.

As more people become employees, they consistently spent less and less time studying freedom or doing anything to maintain it. Government was taken over by a small class of elites.

Freedom decreased.

The elites reassured the masses by telling them that this was good for them, good for safety and security, even good for the economy and their pocketbooks.

The innovative-minded minority protested, but they were discounted as both greedy and extreme.

Today, however, we are experiencing another significant shift, this time in a positive direction.

In short, the most successful careers of the future will include the following characteristics:

- Entrepreneurial

- Independent

- Requiring initiative, innovation, and drive

- Interpersonal rather than hierarchal

- Community-oriented

- Small enough to remain flexible and customer-responsive

- High tech and also very personal

- Leader-driven

These very things also naturally promote a return to the innovative (rather than submissive) view and lifestyle.

If this trend continues, and all indications are that it will boom in the next three decades, we will see an expansion of entrepreneurialism in the economy and also a return to widespread interest in and personal study of freedom by the innovators.

As history has shown, this is a very positive development. It remains to be seen whether the values of the innovators will win the day or be once again drown out by the proponents of submission and dependence.

This conflict, which has been going on since Cain and Abel, will determine the future of freedom.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Among many other works, he is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, The Coming Aristocracy, and FreedomShift: 3 Choices to Reclaim America’s Destiny.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

I find this ongoing battle between the centripetal and centrifugal societal propensities to be fascinating. God’s true will seems to be somewhere in the middle of the two. He wants us to submit to His will unconditionally, but be independent thinkers and self starters.

This is similar to the balance necessary between two forces that creates such useful technology as flight.

Just after writing my last response I read in my core book a chapter about two sets of records. One kept as a record of the temporal history, one of the spiritual history.

It occurred to me that in the temporal side of life, Chris Brady’s Rascal Leader is the ideal; and on the spiritual side of life, the submissive, obedient and compliant person seems to be the ideal.

Of course this does not mean that we do not need both in both submission and independence in our life or that one is more necessary than the other in all of life, but I find it significant that the side if life that trends, in its extreme, toward rugged individualism and isolationism, is kept in check by submission to the side that trends, in its extreme, toward blind obedience.