Much of our recent foreign policy is guided by the notion that spreading democracy will naturally result in a state of peace, and respect for basic human rights.

While seeking peace and human rights are notable and essential goals, the idea of using force to set up a system claiming to foster true freedom is a farce.

Let me tell you a story…

ONE DAY IN NOVEMBER 2001 I received a phone call from a worried Assyrian friend in Detroit.

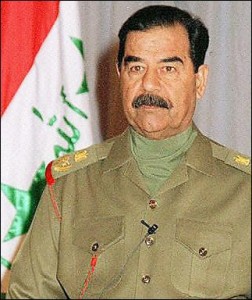

He had been talking to his relatives back in Iraq, “My people tell me that Saddam wants to talk with someone in the U.S., but nobody here will talk to him.”

He had been talking to his relatives back in Iraq, “My people tell me that Saddam wants to talk with someone in the U.S., but nobody here will talk to him.”

I called the US Department of State and spoke to an official (prefers to remain anonymous) who served in Iraq and told me no one from the US had officially or otherwise communicated with Saddam or his regime since 1997, more than four years ago.

Business as usual, I thought.

The ultimate tool of conventional engagement: a huffy silence. I knew my friend well enough to know that he wasn’t calling simply to complain or to voice his worries. He had something in mind.

That something quickly evolved into two “backdoor” diplomacy efforts, first with Iraq’s ambassador to Jordan and secondly, meetings with Saddam’s top officials in Iraq.

Having traveled to many countries, and having met some of the most despotic leaders of modern times, I drew rather firm inferences from these meetings, which I shared at a congressional debriefing after the trip, and later with the administration.

I presented three main points:

1) While Saddam, two weeks before our trip, pounded a podium insisting there would “never be inspectors in Iraq”, I was convinced he would allow inspectors; without conditions. This was based on conversations with then Iraqi Information Minister Muhammed Saeed al-Sahaf, and Foreign Minister Naji Sabri and others.

2) If there were WMDs in Iraq, by the time either our military or inspectors arrived, they would be gone. After all, we announced our clear intentions to go to war a second time, giving Saddam ample time to move whatever he had.

3) We needed to give careful thought to what would come after Saddam. What type of government, resistance, how to deal with the Bath’ists post Saddam, the Sunni/Shiite schism, etc?

Although I briefed several members of Congress, Cheney’s people and the Administration regarding the trip, my words were not fully received.

No Hard Evidence

“How did I know these things?” asked one Senator. I responded that all the so-called intelligence that we were basing a potential war on was only inferences and intuition.

There were no conclusive facts, nor hard evidence. I was surprised that no direct or “backdoor” diplomacy had been engaged, or for that matter all nonviolent efforts at least attempted, since the stakes for the U.S. were very high.

My perceptions were based on the experience of discussing life and death issues with dozens of despotic leaders over 24 years. While I may be somewhat naïve, it is clear that they tend to lie, give false information, and deceive.

While not empirically founded, my perceptions were no more or less pragmatic than what was presented by the Western intelligence sources.

When discussing my thoughts on Iraq with the Bush Administration, it became clear they were not interested.

What proved to be a fateful decision to go to war had already been set in stone, and I simply stood in that path to war.

Jim Hoagland of the Washington Post pointed out:

“The key judgment was made by the Bush Administration in the spring of 2002—that the political status quo could not and should not be maintained in the Middle East.”

A Warning

I will never forget resting on the couch in my home study answering my cell phone. It was the congressman who had helped my undaunted efforts against the war for several weeks.

He gave me clear and chilling advice. “Stop pushing against the Iraq thing. The decision has already been made and your continued efforts could cause you serious problems.”

In my world that type of veiled threat was unequivocal. I would entertain the full wrath of the administration if I persisted.

Regretfully I surrendered to defeat and went on with my life.

I was later to learn that my “file” with the administration, which undoubtedly includes my varied efforts in Libya, Sudan, Afghanistan and Iraq, would catch up with me and present one of the greatest personal challenges of my life.

The Bush Administration’s actions have led, as we know, to a lengthy war on multiple fronts. It will be some time until we are to determine the long-term viability of the fledgling democracies set up within these contexts.

Some countries with large Muslim populations do enjoy stable democracies, such as Indonesia. But in others, the neoconservative bulwark has seen fit to simply clip the wings of democracies who are not “minding their mother,” shall we say, or electing leaders who do not share the values they feel they must.

This was the case in Algeria, and with Hamas in Palestine. Through these situations, we see that democracy is not the ultimate value we are exporting, but a shell of the democracy we hope for.

Universal Human Longing

Step back for a moment and consider the human heart.

Step back for a moment and consider the human heart.

Our essential longings throughout history are not aimed at (or fulfilled) through a form of government such as democracy (or any other), but at a search for universal truth, universal meaning.

The early cave drawings point to human questions about the universe. Our instinctive human passions relate not only to our physical realities, but the spiritual as well.

In our conflicts on this globe, shouldn’t we acknowledge spirituality and the quest for spiritual truth as an essential motivator in the equation?

The neoconservative view that Muslims would welcome a taste of democracy (while at the tip of a gun) is as laughable as Islamic militants offering Islam through the same methods. Force is not the tool that wields true change.

Both attempts ignore the human spirit and respect for each other. If we rather act in such a way to touch a spiritual chord and sound a note of friendship, we have a foundational starting point in engaging each other. For people of faith, faith is infused in everything.

Respect for the primacy of that faith goes a long way in building trust, in laying a roadmap to peace.

Many ask, “But what is this shared spiritual reality? Muslims, Christians and Jews have been diametrically opposed for centuries.”

But we are not so far from each other. When the essence of your religion is caring for the widows and orphans, when you are to love the Lord your God, the Lord who is One; when you preach “if any one slew a person … it would be as if he slew the whole humanity: and if any one saved a person, it would be as if he saved the whole humanity,” we find that we can join together around this rule of compassion for others.

When working as partners and friends in the world, a renewed faith can foster the change of heart necessary in building a foundation that leads to the fruit of peace.

Any hope for sustainable peace must realize the prerequisite of engaging at a spiritual level when human culture and framework is so wrapped in the fabric of the spiritual.

**************************************

Mark Siljander is an ex-Congressman and the author of A Deadly Misunderstanding: A Congressman’s Quest To Bridge the Muslim-Christian Divide.

Mark Siljander is an ex-Congressman and the author of A Deadly Misunderstanding: A Congressman’s Quest To Bridge the Muslim-Christian Divide.

He represented Michigan for fifteen years, which includes three terms as a Member of the United States Congress, where he served on the International Relations Middle East Subcommittee and was Ranking Member of the Africa Subcommittee. He was the primary sponsor of the African Famine Relief Act.

Mark was later appointed by President Reagan as a US Ambassador (Alt. Delegate) to the United Nations in New York, where he served as a member of the Middle East and Africa Strategy Group of permanent representatives.

Ambassador Siljander is a student of several languages, including Chinese, Spanish, Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew, and has spent over ten years studying the three Holy Books of the Abrahamic faiths.

With over 26 years serving in the power circles of Washington and semi-official travel to nearly 130 countries, he has generated unique opportunities for frequent access to world leaders.

These experiences have led him to develop a unique paradigm for the peaceful resolution of conflict that has been successfully applied in several challenging areas of the globe.

Mark Siljander reinforces his conflict resolution efforts through regular travel overseas with Congressional and high-level delegations.

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.