In 1802, one of the greatest musicians in history left Vienna and traveled about an hour’s carriage ride to the small town of Heiligenstadt.

His purpose in traveling was not to meet with fellow musicians, or pursue musical opportunities. He had no family in this small town, and no friends to welcome him.

Rather, he was greeted by loneliness, and stillness was to be his prescribed companion.

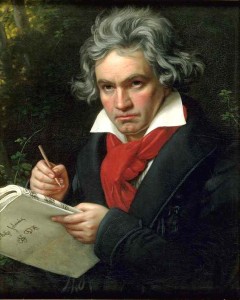

At the young age of 27, Ludwig van Beethoven was experiencing the advanced stages deafness.

At the young age of 27, Ludwig van Beethoven was experiencing the advanced stages deafness.

After six years of agonizing diagnosis and failed solutions, a final recommendation was given: He was to seek rest away from all noise in the hope of recovering at least part of his sense of sound.

Day after day, the one faculty he most valued gradually diminished. Driven to the “verge of despair,” he occasionally sought the companionship of friends.

But even their presence only heightened his awareness that he was going deaf. He returned once again to seclusion.

There Beethoven wrote a will that would come to be known as the Heiligenstadt Testament. The will was addressed to his two younger brothers Carl and Johann, and reveals a man on the verge of desperation.

Nearly suicidal, Beethoven’s letter was written to justify a tyrannical nature and explain a devastating loss.

More than anything, this document unveils the soul of a genius who felt condemned to mediocrity, and the thoughts of a giant who had seen the smallness of his ways.

His words are touched with uncertainty. He wonders how long his life will be prolonged and hopes that his torture will not be protracted, ignorant of the fact that over twenty-five years of life would still be his. He admits hoping that his hearing will return, not knowing that this sense would only fade.

And as an addendum, written four days after the body of the will, he importunes heaven once more:

“O Providence –- grant me at least but one day of pure joy –- O when –- O when, O Divine One –- shall I find it again in the temple of nature and of men – Never? no – O that would be too hard.”

More Life To Live, More Gifts To Give

The lines of the Testament hide the fact that Beethoven’s greatest days were still to be lived, and that his most profound contributions were yet to be given.

That document, kept by its author among his own private papers, never delivered to the hand of family or friend but concealed and most likely reviewed in moments of solitude and solemn reverie, signifies a powerful principle that ought to stand as a symbol on the pages of time.

Beethoven’s life was not easy. From a childhood threatened by a drunken father, to the loss of a mother at age 17, to an adulthood filled with misunderstanding, his personal demons and terrors were real and intense.

The tragedy at Heiligenstadt was not another trial standing in the way of success. This incomprehensible condition appeared to be the one torture best designed to annihilate his very purpose for being.

Without a stable father, or a present mother or supportive friends, he still had a dream. But without the sense of sound, the direction of his life seemed to be confiscated.

A brief decade of success had lit a fire, one that brought warmth and light for some time, but which now threatened to completely consume his soul.

What We Can Learn From Beethoven’s Trials

To what purpose, then was his gift? For what reason was he granted incredible talents, if only for them to be denied before their fullest triumph?

Is the story of the Heiligenstadt Testament an isolated incident of a man and a mission separated by misfortune?

Names such as Joan of Arc, Lincoln, and Churchill seem to indicate that this is not the case.

This story of Beethoven may remind us that our greatest strengths are not our own. It could be a lesson that our most important gifts defy time and circumstance, are never completely innate, and sometimes require tragedy for triumph.

But a serious inquirer might be taught something more. The story of Heiligenstadt does not end there.

Beethoven returned to society. He still grappled with the loss of his hearing. He often quarreled with family and friends.

His failures, after all, were as real as his success. But after the immediacy of his loss had worn away, he began to recall a dream born years before.

As a youth he had read the words of Ode to Joy, a poem by Frederich von Schiller. The first time he heard those words, the lines inspired an intense desire, a hope for untouched joy and perfect peace.

He determined then to set those words to music. But it was not until after Heiligenstadt and all that followed, not until after over 200 attempts to embody those words in musical form that he gave life to the idea that joy is not elusive, but our destiny.

The Power of Submission

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, finished three years before his death, has been recognized as one of the greatest musical achievements of mankind. That setting of Schiller’s Ode to Joy still touches the souls of those who hear it, centuries after its conception.

I wonder if we inevitably seek, in our little, human, finite ways, for those things most likely to destroy us.

And I wonder if God, looking mercifully on, sometimes denies our petty pleas, and grants instead the true desire of our hearts.

Not the desire for recognition, for wealth, or renown. Not the desire for ease, or painless days. But the desires we seldom claim on our own –- the ability to move a world, to lift a nation, to save a soul, things done sometimes unaware, but always out of love.

I do not know if anything less than an inspired perspective could reveal what it is we really want. And I am certain that nothing less than submitting to a Divine will can guarantee us that thing.

And in between those two, the submission and the revelation, for they often seem to come in that order, I expect that there may be found a Heiligenstadt, a guillotine, a fire, a prison, an alter, a garden we do not understand.

The Critical Question

In that defining moment, each person is faced with the question, “How do you know?”

How do you know that truth is truth, when all the world cries out against the premonition, when everything you understand indicates that you might be very, very wrong, and all eternity hangs in the balance, how do you know?

The answer defines our service. The answer defies our world.

Our greatest certainty should not hinge on consensus. Our deepest joy cannot be bound by man. Our surest conviction ought to be worth more than sight, than sense, than sound.

Heiligenstadt led Beethoven to the truth that our best gifts are God-given, as is their perfect use, and the terms of our success. And despite what man may say, or we may feel, there is eternal consequence that confounds the wise, and recognition that is beyond this world.

Lines from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony indicate that only an unearthly object can ever satisfy our earthly efforts. Only a certain mind will seek such a visionary goal.

Dwells above the canopy of stars.

Do you sink before him, millions?

World, do you sense your Creator?

Seek him then beyond the stars!

He must dwell beyond the stars.

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.